View larger

View larger

Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743)

Demande d'informations

| Oil on canvas |

| 82 x 66 cm |

| Delivred in 1701 |

More info

1/ identity of the sitter :

The portrait depicts Édouard Colbert (1628-1699), Marquis de Villacerf, Superintendent of the King's Buildings between 1691 and 1699.

1.1 Biographical details:

Édouard Colbert was born on 5 February 1628 in Paris and baptised the same day at Saint-André-des-Arts. He was the son of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Marquis de Villacerf et de Saint-Pouange, and Claude Le Tellier. His brothers were Gilbert Colbert de Saint-Pouange and Jean-Baptiste Michel Colbert de Saint-Pouange. He is the nephew of Chancellor Le Tellier and the first cousin of the Marquis de Louvois. He belonged to ‘that branch of the Colbert family that remained loyal to the Lizards’ (Thierry Sarmant).

He was titled Marquis of Villacerf and Payens, seigneur of Saint-Mesmin and Courlanges, la Cour-Saint-Phal, Fontaine-lès-Saints-Georges and other places.

On 13 November 1658, he married Marie Anne l'Archer (?-1712). The couple's sons were Pierre Gilbert Colbert (c. 1671-1733), Charles Maurice Colbert known as the Abbé de Villacerf (c. 1675-1731) and Anne Marie Geneviève Marguerite Colbert (?-1696).

He was first butler to the Queen (1666), first clerk of War under Michel Le Tellier and then Louvois (...1686), general inspector of the King's Buildings (1686-1691), superintendent of the King's Buildings (1691-1699), first butler to the Dauphine (1697). However, he was forced to resign as superintendent of the King's Buildings in 1699 because of embezzlement by his first clerk, Mesmin Pierre.

He died on 18 October 1699 in Paris and was buried on 20 October at the Minimes de la Place royale.

Bibl.: François de Colbert, Histoire des Colbert du XVe au XXe siècle, Les Échelles, published by the author, 2000; Thierry Sarmant, Les demeures du soleil : Louis XIV, Louvois et la surintendance des Bâtiments du roi, Seyssel, Champ Vallon, 2003, p. 91-93; Thierry Sarmant and Mathieu Stoll, Régner et gouverner : Louis XIV et ses ministres, Paris, Perrin, 2010, p. 290-291; Eric Thiou, Dictionnaire biographique et généalogique des chevaliers de Malte de la langue d'Auvergne sous l'Ancien Régime, 1665-1790, Versailles, Mémoire et documents, 2002.

2.2 Rigaud's client:

In Hyacinthe Rigaud's account books (see Ariane James-Sarazin, Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743), Dijon, Faton, 2016, n° *P.744, p. 248), a ‘Marquis de Villacerf’ is listed in 1701 for a 150 livres portrait, i.e. a bust. In 1919, Joseph Roman suggested that Édouard Colbert should be included. In 2016, we rejected this identification in favour of that of his son, Pierre Gilbert Colbert, insofar as on the next line of the account books appeared the mention ‘Monsieur l'abbé de Villacerf son frère’, which seemed to refer, in view of the title, to Charles Maurice Colbert (circa 1675-1731) and not to Jean-Baptiste Michel Colbert (1640-1710), archbishop of Toulouse. In addition, the fact that Édouard Colbert died in 1699, two years before his portrait was entered in the account books, also supported this correction.

We now believe that we should return to Roman's proposal, for the following reasons:

In 1919, Roman pointed out the existence of the original portrait of Édouard Colbert in the home of the Duc de Doudeauville at the Château de Bonnétable, where the painting originated. Sosthène II de la Rochefoucauld (1825-1908), owner of Bonnetable, inherited the estate from his brother Stanislas (1822-1987), who had married Marie Sophie Adolphine de Colbert and died without issue. The latter descended from Gilbert de Colbert (1642-1706), the model's brother.

There are other examples of retrospective portrait commissions in Rigaud's oeuvre, and it is likely that either Édouard's brother, Jean-Baptiste Michel, or Édouard's son, Charles Maurice, wished to commission their portraits in pendant and bust form, for the same sum, in 1701, in memory of either a brother or a father.

The age of the figure depicted is entirely in keeping with the age reached by the Marquis de Villacerf when he died in 1699, i.e. 71. Rigaud's distant gaze is perfectly suited to the portrait's retrospective status, and suggests a distance from the afterlife.

The salient features of the figure's physiognomy are consistent with those found in the various known effigies of the Marquis (see the images attached to this document following our analysis).

There was therefore certainly an error in the entries in the account books, which are far from free of errors: either the 2nd Colbert de Villacerf painted is Edward's brother, or it is his son.

Finally, it should be remembered that unlike the Louvois-Le Tellier family, whose effigies are not plentiful in Rigaud's painted work, the Colberts and their relatives were regular customers, and thus unfailing supporters, if not protectors, of Rigaud (see on this subject Ariane James-Sarazin, Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743), Dijon, Faton, 2016, tome 1er, p. 104, 119-120, 314-315, 626).

2/ pictorial analysis :

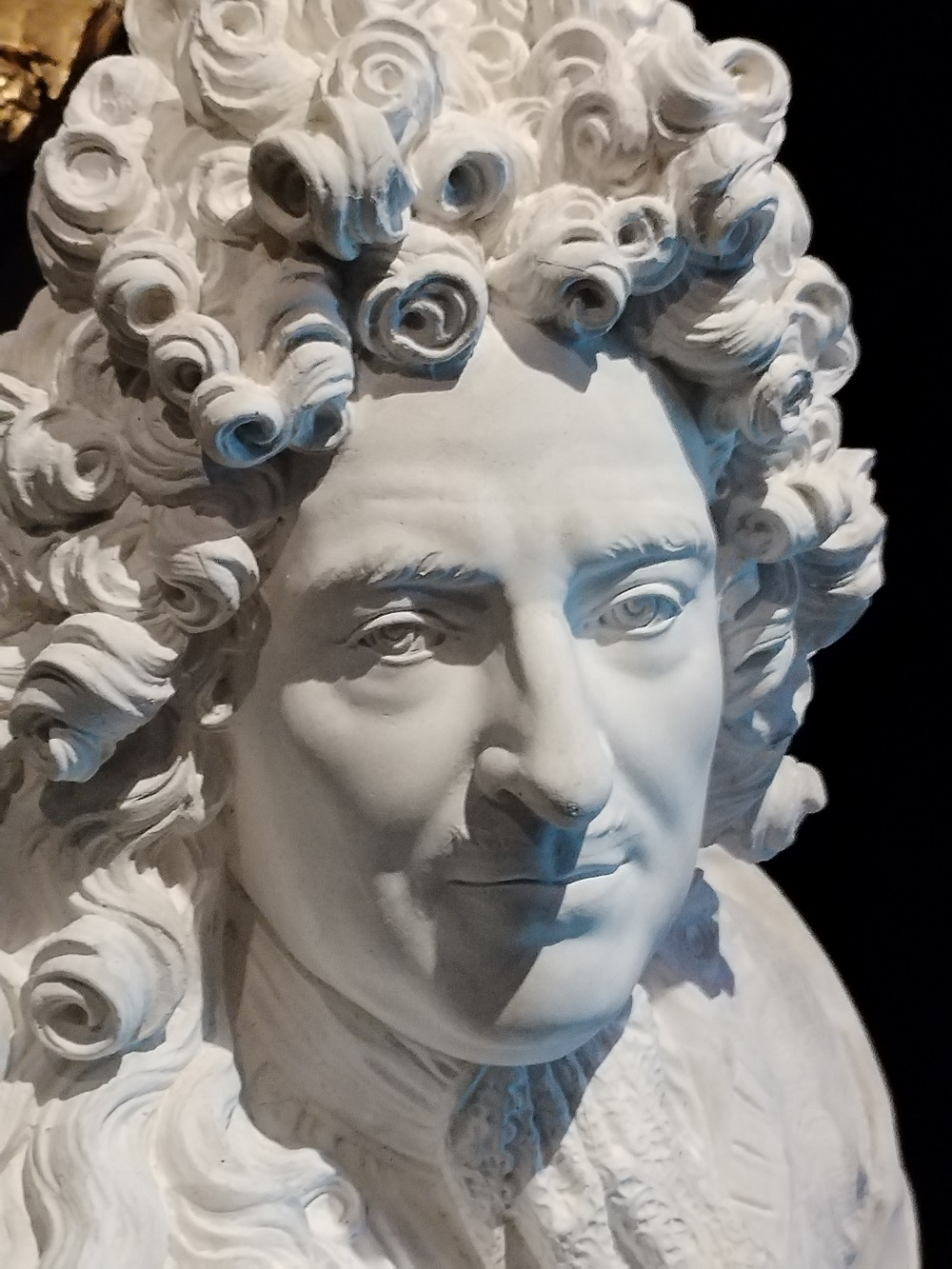

A bust typical of Rigaud's work in the 1690s, with even a hint of retrospection, which we believe the artist sought, even though the portrait was commissioned in 1701:

Sobriety of composition;

Characteristic embroidery along the bottom of the coat;

Reverse effect, with a grey/black hue that could aptly evoke the disappearance of the sitter;

Very simple tie;

Neutral, dark background.

High, abundant wig from the late 1690s and 1700s.

All the characteristics of a full Rigaud autograph are present:

Extreme sharpness and accuracy in the rendering of skin tones: the old man's fine, wrinkled skin looks like silk paper;

Acuity in the rendering of every physiognomic detail: age marks under the eyes; traces of the moustache, out of fashion; bushy eyebrows;

Sensitive psychological approach;

Noble bearing and air;

Rounded and marked outlines of the folds as in the portraits of the 1690s, as if Rigaud wanted to adopt a retrospective style which he abandoned in the 1700s, the decade of maturity of his style;

Work in the paste that confers presence and relief, while catching the light;

Visible brushstrokes.

Finally, it should be noted that Rigaud used the same range of colours for the mantle as for Mignard's bust. It is worth remembering how close the two artists were, Mignard having supported his young colleague in the face of recriminations from the guild of master painters in Paris, and then from the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The 1690s betray these elective affinities between the two artists, including in Rigaud's pictorial biases.

Ariane JAMES-SARAZIN

Our painting comes from the Château de Bonnétable in the Sarthe and belonged to Sosthène II de la Rochefoucauld (1825-1908). He inherited it from his brother Stanislas de La Rochefoucauld (1822-1987), who had no descendants and kept it at the Château de La Gaudinière in the Loir-et-Cher. The latter had received it from his wife Marie-Adolphine de Colbert, a descendant of the patron Gilbert de Colbert (1642-1706), brother of the model.

Unlike the other known portraits of Edouard Colbert de Villacerf, notably by Mignard in painting and by Martin Desjardins in sculpture, in which the Superintendent of Buildings is presented to us in the prime of life, with a stern face and an authoritarian air, in keeping with his high office, Rigaud offers us a more intimate view with our painting.

The painting was delivered two years after the death of the model. As Ariane James Sarazin suggests, it would be a post-mortem portrait commissioned by his brother Gilbert de Colbert, who was then living in the same street as the painter. Rigaud endeavoured not to betray the memory of his patron's brother, and it is with this affectionate and sincere gaze that he depicts him at the twilight of his life. One cannot help but admire the talent with which Rigaud admirably depicts the moist eyes, the fine wrinkled skin, the bushy eyebrows, the slightly recessed upper jaw and above all the serene air of a person at peace with a fulfilled existence. Far from flattering and grandiose portraits, Rigaud chooses for this singular painting an effective composition and a sober palette that focus our attention on this face rendered truthfully without idealisation and on the depth of the gaze of his respectable model.

Edouard Colbert de Villacerf ended his days in a great despair that aged him, emaciated him until he finally got the better of him. The man that Rigaud portrays with his characteristic psychological precision is indeed the man described by Saint Simon:

‘Monsieur Villacerf could not survive the misfortune that befell him through the infidelity of his chief building clerk, whom I mentioned at the beginning of the year. He had not been in good health since then, had not set foot in court again since leaving the buildings, and finally died. He was a good and honest man, already old, and unable to get used to having been deceived and to being nothing anymore. He had lived a long life, always on extremely good terms with the king, and so familiar with him that, having been at one of his former games of real tennis, at which he played very well, a dispute arose over his ball; he was against the king, who said that all they had to do was ask the queen, who could see them playing from the gallery: ‘By...! sire, replied Villacerf, that's not bad; if it's up to our wives to judge, I'll send for mine. The king and everyone else present laughed heartily at the remark. He was a first cousin and enjoyed the utmost and most intimate confidence of M. de Louvois, who, with the king's knowledge, had involved him in many secret matters, and the king had always held him in high esteem, friendship and regard. He was a brusque man, but frank, true, upright, helpful and a very good friend; he had many, and was generally mourned and missed’

(Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon (Adolphe Chéruel (ed.), Mémoires du duc de Saint-Simon, 1856, vol. II, p. 320-321).

Pierre Mignard, Portrait d’Edouard Colbert, marquis de Villacerf, 1698, Versailles

Martin Desjardins (1637-1694), Portrait d’Edouard Colbert, marquis de Villacerf, 1693, marbre, H. 70 x L. 80 x pr. 47 cm, Paris, musée du Louvre, inv. MR 2172

Avis

Aucun avis n'a été publié pour le moment.